Price discrimination is a way that companies can make more money by understanding how much different consumers will pay for the same good. Here's how it works.

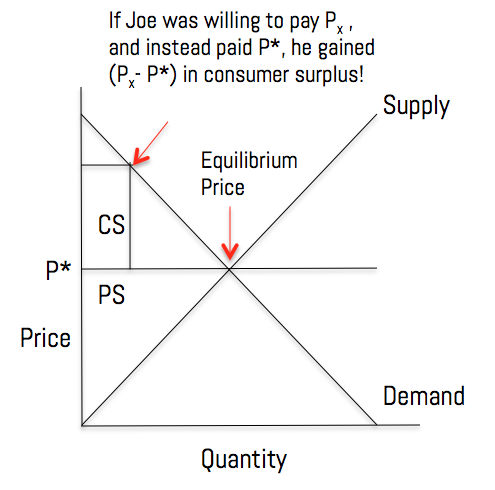

In economics there is a concept called willingness-to-pay, which I’ll refer to as WTP for brevity’s sake. An individual’s willingness to pay is simply the maximum amount they are willing to pay for a certain thing. Straightforward enough, right? If a customer was willing to pay $20 for a book and it only cost $15, they have profited by $5. This is referred to as consumer surplus. The difference between what an individual is willing to pay and what they actually pay (if positive) is individual consumer surplus.

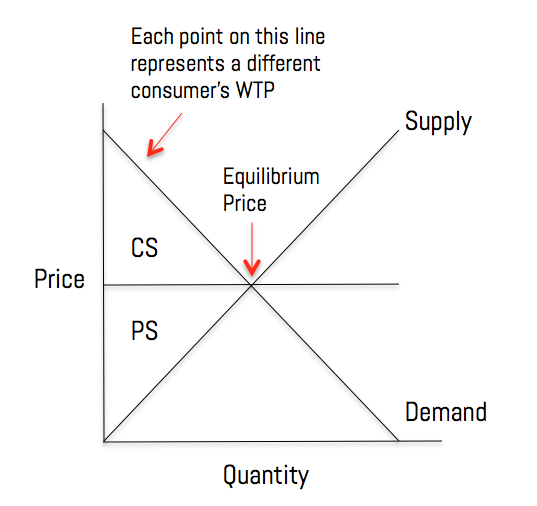

Represented graphically, a point on the demand curve hypothetically represents each person’s WTP. If the difference between this point and the actual price is positive, the consumer has some surplus!

But, imagine if a company could charge each customer at the exact amount they were willing to pay! The company would capture all of the consumer surplus as its own profit! As it happens, virtually every good is not priced at individual WTP. This would be perfect price discrimination, and much to the chagrin of companies, is not a realistic possibility right now. After all, how could a company actually know what each customer was willing to pay?

Even though companies cannot practice perfect price discrimination, they can capture additional profit (in the form of consumer surplus) by price discrimination of lesser degrees. Though the categorization / labeling of these different types of discrimination is debated, for the sake of clarity I will group them under three traditional labels.

First Degree Price Discrimination

First degree price discrimination is what I described above - perfect price discrimination, where you charge each customer a different price for the same good. This is impossible for almost all industries. Producers can charge at individual WTP in auctions (eBay), or "name your price" businesses, but these are individual examples and not scalable. This is why first degree price discrimination is rare / non-existent.

Second Degree Price Discrimination

Second degree price discrimination is quality or quantity-based, that is, charging different prices based on quantity or quality.

Air travel is a great example of second-degree price discrimination. Offering individuals a set package of goods and allowing them to self-select out from there is second-degree price discrimination. All individuals buying an airline ticket will be taking a plane somewhere, but some will be sitting with extra legroom, have a first class seat, or buy in-flight services like food or wifi. Had the airline included the cost of internet, food, and a roomy seat in every ticket, some budget travelers would perhaps not buy a ticket at the higher price. By offering a set package with additional options, the airline can capture consumer surplus from people who are willing to pay more for a comfortable flight experience.

Second degree price discrimination includes bulk and bundled discounts, as well as time-based discrimination. Sometimes bulk discounts are combined with a two-part tariff (another kind of price discrimination). A two-part tariff is when a customer has to pay an upfront fee for membership or a similar designation, then pays additional fees for goods and services rendered. A Costco membership is a two-part tariff—one pays to join Costco or Sam’s Club, then pays for the items they buy, with the caveat being that these goods are cheaper than at other resellers due to bulk / bundled discounts. Amazon Prime membership is also a two-part tariff, as is belonging to a country club (and many other clubs) or having a museum membership. Companies gain because they not only collect money from the entry fee, they also make more money because customers purchasing a membership or what have you plan on using this service more often (increased business!).

Third Degree Price Discrimination

A seller can practice third degree price discrimination by segmenting their market into groups that are willing to pay different prices for similar or the same good. Charging different prices based up on gender (clothing) or age (tickets for many goods, meals for the elderly, etc.) can capture more consumer surplus.

How? Well, if males and females both were charged $40 for a shirt, many males would say “that’s way too much money, I don’t care about clothes”, and simply not buy the shirt. By charging lower prices for men’s clothing and higher for women’s (who presumably are willing to pay more for fashion’s sake), a seller is able to make more sales than otherwise while still making more money. Same goes for charging prices based on age, although this arguably can also be inter-temporal (time-based) price discrimination. Giving discounts to people who come eat at 5 o’clock (early bird specials!) helps a restaurant make more money throughout an otherwise-slow time, and simultaneously attracts customers who retire earlier in the day—the elderly, or perhaps those with small children. Student discounts have a dual purpose—they make companies appear sympathetic to a financially-strapped group, while they also encourage more students to patronize businesses than otherwise would. It can seem counter-intuitive to charge less for some customers, but by doing so a company will usually gain more customers overall, offsetting any profit loss.

Another (more rare) form of segmentation could be geographic. An energy company could charge customers in the North more for winter heating than customers in warmer Southern regions.

Inter-temporal Price Discrimination

As the name might imply, inter-temporal price discrimination involves charging different prices at different times for things. This could apply to travel (last minute costs more), clothing (wait for sales), and other goods.

What do TJ Maxx and Neiman Marcus have in common? Both benefit from inter-temporal (time-based) price discrimination. Luxury stores like Neiman Marcus or Nordstrom capture customers who are willing to pay high prices now, while their counterparts Neiman’s Last Call and Nordstrom Rack get customers willing to wait or be “out of season” for lower prices. Other discount stores such as TJ Maxx appeal to individuals willing to wait to buy the same good at a lower price. These stores have identified their target market, what they are searching for (high-end fashions this season, versus high-end next year), and they use this information to their advantage in their business model.

What is needed to practice price discrimination?

In order to effectively price discriminate, you need to know about your customers and market. Information on who they are, what their flexility for pricing is (price elasticity of demand), and how many other people offer a similar thing to you. To put these requirements into a formal list:

1) You must be a price-setter. If you are Starbucks in the coffee industry, the prices you set will usually hold. If you are an independent coffee shop, chances are, you are not a price setter and your customers will go elsewhere if you increase prices. In order to practice price discrimination, a company must have enough power in the industry or market to change prices, not respond to them.

2) Customers must have differing price elasticities. If all your customers react to changes in prices the same way, price discrimination will not work. The idea is that price elasticity represents how sensitive you are to changes in prices, and a student might be more sensitive to a price increase than a middle aged individual.

3) These differences must be recognizable. The differences don't matter if you cant tell they exist! It's easy to identify wide generalization about price elasticities, but within a given group there might be hidden differences that a business cannot see. If you can't see the differences, you can't successful exploit them.

4) You must be able to prevent arbitrage. Arbitrage in this sense involves buying a good at one price and selling it at a different one to another person who for some reason couldn't get the same price. This might include buying a student ticket to a movie for $11 and selling it to an older person for $12 (as opposed to the regular fare of $13). This example seems ridiculous, but is relevant on a larger scale. Apple could never successfully charge consumers in China more for iPhones than in the US, because people in the US would just go sell their phones in China to make money. This is a thing that happened during the iPhone 6 releases (selling phones because they were unreleased).

With all this in mind, you can analyze the actions of companies to see how they might reflect hidden motives. For example:

When Netflix started offering the ability to add multiple users to an account, they were not actually trying to be helpful to the customer; they were trying to gauge how many people were using a given account in order to more effectively target customers in the future.

Everything a big company does is designed to somehow make it money in the future. Now that you understand price discrimination in its various forms, corporate actions may start to take on new meaning. Go forth and analyze!

Money represents a social agreement, which has implications for how we value wealthy people. Bitcoin replaces the need for this social agreement with technology, and in doing so challenges the values we ascribe to wealth.