First of all, the term "brand relationships" is not one that would have made a lot of sense before the dawn of social media. Outside of ad agency doors, few would describe their feelings towards a company as part of a relationship in any sense of the word. There was customer loyalty, sure. But the only connection a brand had to consumers - both potential and existing - was through stagnant ads. Billboards, print advertisements, and TV commercials were the default modes of advertisement for decades. The only problem is that we have no idea if they work, and no ability to provide information relevant to a particular person. Granted, this is an ability still lacking - most ads you see are irrelevant - but the future holds hyper-targeted, personalized, and relevant advertising, powered by the mass of data we generate online (and simply by existing).

Consider the state of advertisement in 2016 to be step 3 of a staircase I can't see the end of.

Ground Floor:

The extent of targeting is by time of day an ad is shown (television) or the publication / channel is it shown in (women's magazine versus golf publication). There's more nuance to the evolution of ad targeting than this, but for the sake of simplicity I will just take a pre- and post- internet look.

Step 1:

The early internet brings about the ability to target audience in a way never seen before. Websites provide a much more specialized audience, and email campaigns allow a more direct messaging avenue. The early web also brought cookies to the world.

Cookies, formally known as HTTP cookies, were created in 1994 at Netscape (fun exercise: try Googling "who created cookies" and finding a single HTTP related result). Cookies are what power basically everything that makes the internet convenient (saved logins!), as well as allowing content providers, merchants, social networks, and of course, advertisers to understand who is viewing their stuff. Cookies are basically little nuggets of data stored in your browser when you visit a website, and sent to the server (which you can consider the physical presence of a website if it makes things easier to picture) whenever you revisit the site. Thus, cookies can tell a site where you are coming from, what you did on that site in the past, if there is relevant advertising to show you (those ads of products you just looked at), and more. But in the early days, the applications of cookies were not nearly as advanced.

A company named DoubleClick was founded in 1996, which focused on Internet ad serving for big customers. DoubleClick's technology involved the use of HTTP cookies to understand who users were. DoubleClick was later acquired by Google, and is what powers the user insights you can get in Google Analytics. For those who haven't used Google Analytics, it can tell you age segments, interests, location, gender, and more about your website visitors. They approximate these values based on browsing behavior tracked by DoubleClick, Google's info on users, and more. (It's kind of a black box.)

The launch of Google Analytics is about where Step 2 begins.

Step 2:

With the advent of hyper-targeting and user segmentation, websites no longer had to estimate who their audience would be based on content material. Even though cookies already existed, in the early internet days small content publishers did not have these analytics. Google Analytics, by the way, is free. So, anyone who cares to do minimal digging has customizable reports and a wealth of data at their fingertips.

Major content creators, both on desktop and mobile, know everything you do on their site, down to the millisecond. Check out the below heatmap of Facebook usage. Usage can be visualized in many different ways, but the point remains that content providers know everything you look at, click on, etc. (Kinda - an issue with digital advertising, as with all kinds of advertising, is that they have an estimated amount of views based on page views, but there is no guarantee the visitors actually *looked* at the ad. Unless the device is doing eyeball tracking, which I hope doesn't happen anytime soon, there is no way to know if your ad was truly seen. So, some transparency, but not as much as ideal - unless you're the one selling ads based on inflated view counts, thereby making more money than you should be.)

Despite all the intel advertisers have, ads remain a clearly different thing in your feed from your friends' content. Either their ad directors or their targeting still really stink. Even at Step 2 with advanced intel about online habits and personas (you can buy mobile data from AT&T and huge persona sets from data-brokers, revealing what ad persona everyone is) our ads remain obviously ads. Brand identity is weak for most brands, and we all roll our eyes when Clorox tries to ask you how your day is.

Things are rapidly changing, though. Notice the way that Facebook and some other services talk to you. "What's on your mind?", "How are you doing?", "Good morning!"

Very personal, very human. This is no accident. The web and most of the mobile ecosystem as we know it are a strange thing. Humans have communicated in 1:1 way for all of our history until recently. Suddenly, your interface with information is through this "browser", or a single-function app, and you search through clicks and buttons and more to find what you want. Booking a table on OpenTable is a step up from calling the restaurant, but what if you could just send a message to OpenTable asking for a table at 7 pm, and book within the message? What I'm referring to is conversational UI, or messaging UI, or whatever people are calling it now. There is a huge amount of buzz around conversational UIs, and how having conversations with brands & services right next to your friends is the most native, easy, and natural way to do things. (Read more on conversational UIs here, here, here, and here.)

from Wired.

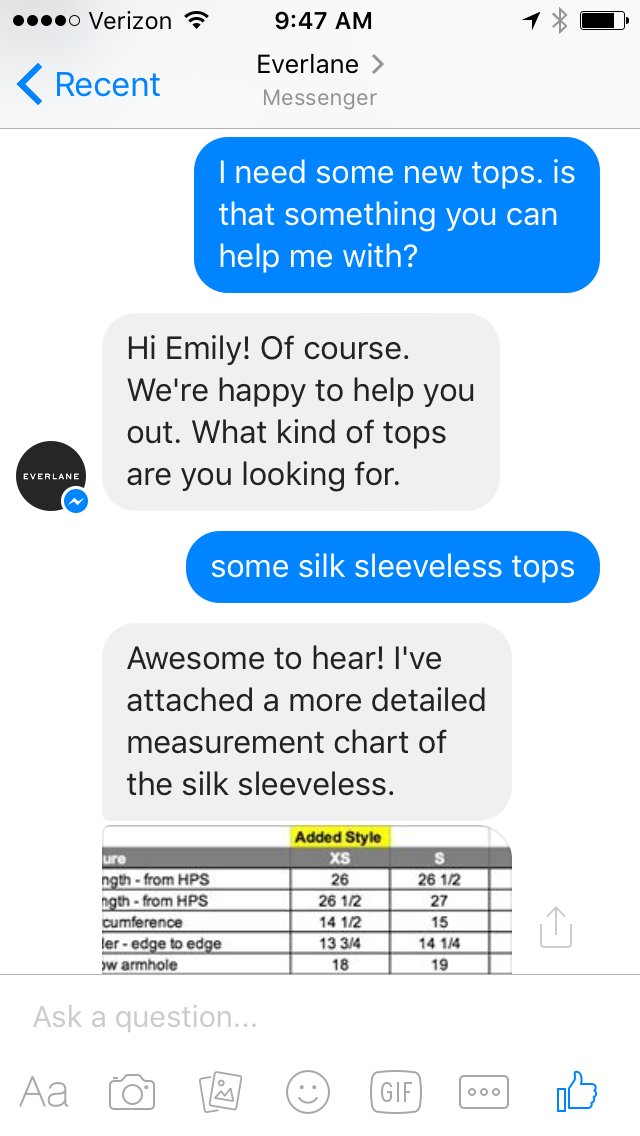

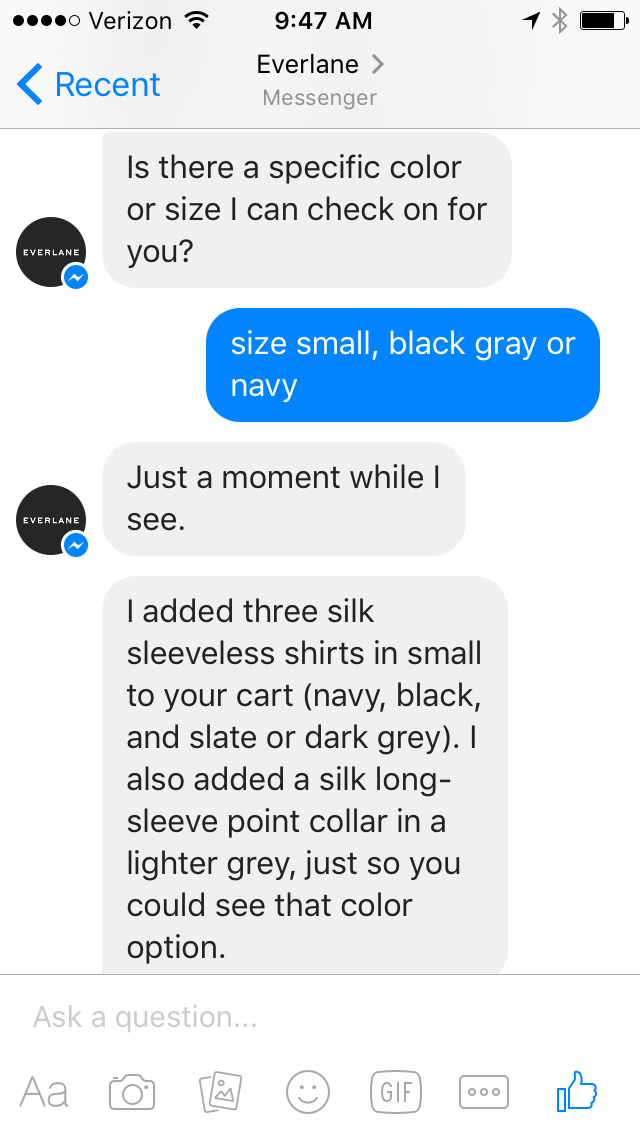

I've heard a lot of talk about the benefits of conversational UIs for customer onboarding, simplicity, and "naturalness". (See above!) But, I've yet to hear much about how conversational UIs will change brand relationships and advertising. I think this change is a very significant one. Facebook Messenger is now allowing brands and services to have a chat channel where they can connect with customers and do business. As you are ordering your new clothes from Everlane, your best friend is messaging you in the conversation box below. Brands have NEVER, EVER, been so close to your personal life and social relationships. Check this out, from Tech Insider:

Emily is buying clothing from a brand, while having a conversation (how things have always gone before the internet), in a way that is highly mobile optimized.

"For the majority of online retailers, north of 60 per cent of their website traffic is mobile - but only ten to 12 per cent of checkouts are mobile. And mobile traffic will continue increasing. So the thought is, what would those interactions look like if the web and desktop had never existed?" -David Marcus, head of messaging at FB, Wired

Again, this reinvention is largely focused on optimizing how we do business on mobile devices. Conversational UIs are most relevant for phones, because desktops are whole mess of random UI decisions and ways of doing things that don't really align with human needs. Also, we use our smartphones more and more, and desktop/pc devices will probably become less and less important as computing fades back into the fabric of society.

We got the idea for conversational UI from China and the East in general. The East is the new West when it comes to mobile technology, because they entirely skipped the PC era. Smartphones and mobile data are what first connected the majority of people in the East (those that are connected, that is). They never had the concepts of desktop computing shaping how a brand made their app, and more importantly shaping the way consumers feel comfortable doing business. In the immensely popular Chinese messaging app WeChat, you conduct transactions and have conversations in lines right next to each other. Channels can be customized by brands - you can book a limousine, apply for a mortgage, buy movie tickets and select seats, and so much more, all in the same app. This one app holds millions of services inside it, and customers don't have to download a whole new app to do another function. A WeChat account is more important than a website for many Chinese brands.

These brands live next to your friends, and WeChat or Facebook Messenger right now aren't even great examples of a brand personifying your relationship.

But Snapchat takes brand relationships to a whole new level, a level I think will eventually be present in all of our brand-human interactions. Any brand, website, celebrity, or politician can have a Snapchat account. For younger brands, Snapchat is *huge*, especially for online-only content publishers like Buzzfeed and Refinery29. Snapchat has access to the youngest audience of any app, and users are constantly using Snapchat. They are a great example of how internet companies are pretty much solely valued on the potential of their userbase:

Vine has as many monthly average users as Snapchat, but the users tend to be lower-income and minority. Plus, VCs rely on their exposure, and their kids are more likely to be using Snapchat than Vine. Instagram vs. Vine usage faces the same plight. This phenomenon is similar to the flight from Myspace to Facebook as Myspace became "ghetto" (not my words). Our technology, intended to be neutral, reflects our societal biases.

I’ll interject here that there is a lot of criticism to be had for the metric of MAU. Medium just wrote a great post on this. Vine benefits from “users” watching videos embedded elsewhere, while Snapchat users only exist in their ecosystem. Number of monthly users hardly reflects quality of usage, time spent, etc. But the point remains — both are very popular, but have wildly different valuations.

Biases aside, the value of many services is more based on their userbase than their product. Snapchat is worth nearly $20 billion because it has access to the youngest userbase of any app, and they are always around. WhatsApp has incredibly standard functionality, but an incredibly un-standard user-base — they just hit 1 billion users, and many of them are located in emerging countries. Countries, notably, with a much lower Facebook penetration rate than the US. Facebook paid to have a big slice of both the messaging market and access to the emerging market. (Oh, and WhatsApp has announced they’ll be free now, and making money from having brands use the messaging service. Sound familiar?)

Point of all this being, Snapchat has a really valuable audience, an audience too young to have formed hard-and-fast habits of content consumption and e-commerce expectations. Snapchat has focused their efforts on becoming a new content platform, with decent success, and has ignored the commerce angle for the most part (minus Snapcash, does anyone use that? Would love to see statistics). The most important phenomenon on the Snapchat platform, though, isn’t even one they are making money off of.

Brands and websites have Snapchat channels. Your (you being the typical Snapchat user, let’s go ahead and say a 16-year-old girl) favorite Instagrammers have Snapchat accounts. You love to follow their lives, they are so pretty and stylish and live these amazing lifestyles. You watch all their Snapchat stories religiously. Your favorite Instagrammer announces that she will be doing a Snapchat takeover for Refinery29 during a music festival. You add Refinery29, because you want to see what goes down. Refinery29 is a brand, a content provider, but they have someone you think you know well live-streaming their activities. Refinery29 chose the Instagram star because of their aesthetic and audience. They think the Instagrammer aligns with their brand image.

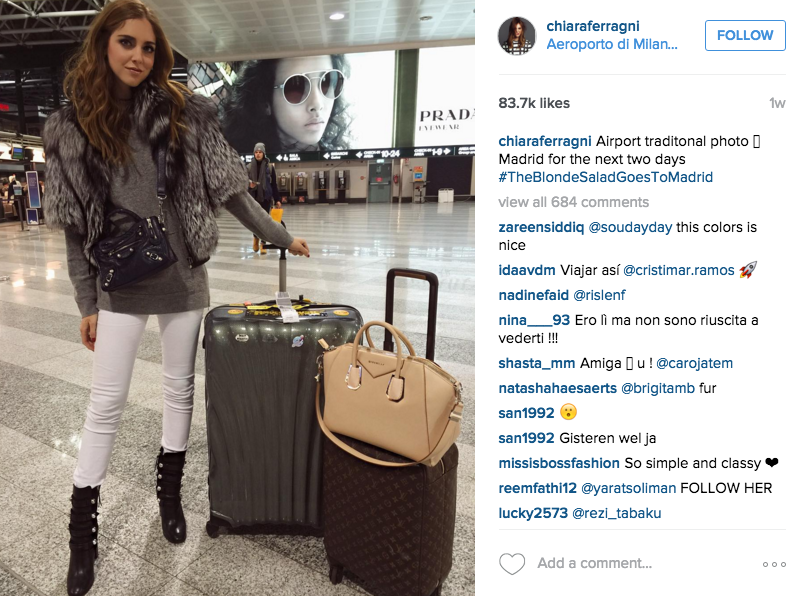

Above: Chiara Ferragini, blogger/model/generally a person you are envious of. She is always shooting something new, promoting a brand or taking over a Snapchat, promoting her own Snapchat, promoting herself, or promoting her shoe/accessories line. Note the W Mag Instagram takeover, invitation to view her becoming face of Pantene on Snapchat, and general work to establish that she lives the life you want to.

Brand reps are nothing new — perfume, hair, makeup, and clothing companies have famous ones all the time. But we didn’t/don’t obsess over the star in the same way, we don’t have access to them in the same way. When the Instagrammer takes over Refinery29’s snapchat, or a clothing brand’s snapchat, she is getting paid to represent the values and aesthetic of that brand. You, the fan, are seeing your favorite Instagrammer, your girl crush, as she represents what it means to go on this website or wear this clothing brand. This isn’t just a 30-second commercial or one page spread. This is segmented live-streaming, what feels like an intimate connection.

For that hour (or whatever), the Instagrammer is supposed to represent the brand, and hopefully rub off a bit of their cool onto the brand. Oh, and you’re looking at the brand’s stories just a few seconds apart from those of your close friends. Not only are brands hosted next to your friends, they are viewed — willingly! — in the same social context as your friends.

The brand becomes human, the brand takes on the persona of the “famous” and beautiful internet stars and models they pay to represent them. Most insidiously, because you consider that beautiful Instagram star to be your friend in a way, the brand is becoming your friend.

My mind is continually blown at the close access brands have, for free, to users. It’s the equivalent of if someone really attractive came up to you, engaged you in a great conversation, then started talking about how great Colgate toothpaste is. Except on Snapchat, it isn’t weird at all.

As time goes on, brands may have internet stars streaming their lives, lives that are in accordance with the brand’s values. By humanizing the brand, they grow appealing to younger generations and create a kind of discourse that blurs the lines between market and social relationship. This phenomenon is in it’s early infancy, but this is the Step 3 (transitioning to Step 4) I’ve been hinting towards. Brand-consumer communication becomes a more social and conversational relationship, integrated within the same platforms as basic social functions. Ultimately, this leaves room for more and more people to become brands themselves.

When brands hired reps in the past, the brand borrowed that person’s image. That weightloss supplement doesn’t have a persona, the celebrity hawking it does. When brands use young, internet-famous people who don’t really have a career of their own, the brand becomes the image more so than the reverse. Take the Victorias Secret Angels, who are more Angels than they are models. Their tagline is forever related to being an Angel. Today the Angels are one of the few pervasive brand identities. But in the future, we could see popular Snapchat and Instagram accounts having something similar to Angels — people who rep their values, the life their users want to have, all in real-time.

Combine this closeness with the growing ease of Natural Language Processing (NLP), AI abilities, and the wealth of data we generate online, and hyper-targeting becomes possible and affordable. Brands can develop personas tailored specificially to you, a relationship that only exists between the brand and you. We go from Step 3 — intimate brand access, but on a general level — to Step 4.

Step 4:

Imagine a future in which you can’t tell if someone is a brand or your friend. Imagine a future in which Buzzfeed sends you a Snapchat or message to let you know they have an article they think you’ll like — and they’re ALWAYS right! Imagine a future in which an online clothing brand sends you a message and link: “This reminds me of your style!”

The brand/user relationship trickles down to a 1:1 level. You have a relationship with the brand that is unique to you. They provide marketing, conversation, content, whatever — just for you. There is room for more people to become brands, and also a distinct digital record of you.

If I’m going to get really dystopian, perhaps there is a central data broker that holds all the information about you. Brands have a general strategy for user interaction, and plug in specific peoples’ information profile to spit out the personalized version. It seems rather inevitable for personal data to become increasingly centralized. Google, Facebook, the cell companies, and data brokers like Acxiom all have huge amounts of personal information. But, the scattered nature of our personal data right now means no one actor has a complete picture (if they ever could). Perhaps each of them will continue to collect more data and carve out their own market segment, but that would mean advertising remains more irrelevant than it needs to be. In order for advertising — the biggest priority for like, everyone ever — to improve in effectiveness, data will need to become centralized.

Now, I’m not actually positive that people will allow brands to become that close with them. Yet, they don’t realize just how close we are to that vision.

Regardless, the trend of brands developing social relationships with customers is an unprecedented and significant one. It reminds me of an article I read about tech taking us back to a village lifestyle. It was mainly sharing economy psychobabble, but I see a parallel here. In 1850 you had a social relationship with the owner of the general store, in 2025 you’ll have a social relationship with Revolve Clothing.

Money represents a social agreement, which has implications for how we value wealthy people. Bitcoin replaces the need for this social agreement with technology, and in doing so challenges the values we ascribe to wealth.